Editor’s note: I have officially rebranded this Substack to align with the upcoming launch of my offline-only record label Muse Foundry. This is part of a larger project to restore music’s role as a symbolic, epistemological, and ethical force in culture and to resist the enclosure of human expression by scalable, data-driven systems.

Three Colors: Blue

I was sitting on my couch this weekend and had a vivid memory of being a teenager and walking into Blockbuster Video and randomly renting a foreign film called Three Colors: Blue by Krzysztof Kieślowski¹. When I returned home I placed it into my VHS player and remember thinking after about the first 30–40 minutes of the film ‘wow I didn’t know you were allowed to live this way.’

There was something more in this memory though, so I took this as a summons and watched the film again for the first time in 30 years. This time, I could finally name what my teenage self had sensed:

Music doesn’t accompany life but actually calls it forth

What Seeks to Sound Through Us

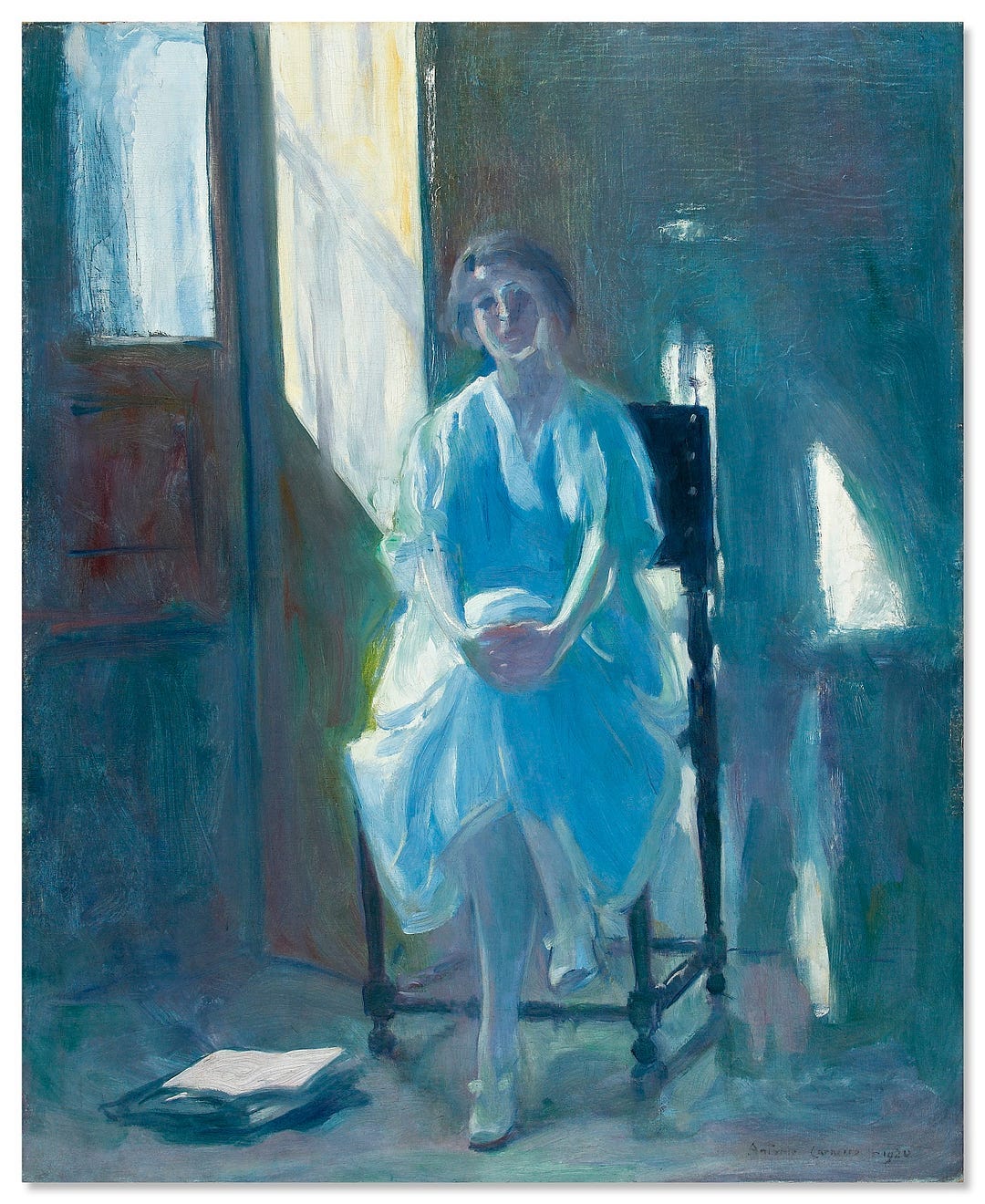

Julie (Juliette Binoche) loses her composer husband and young daughter in a car crash. At the funeral, which is broadcast on national television, we discover her husband was a famous composer. He’d been commissioned to compose a musical work celebrating European unification after the Cold War, which the public and the characters surrounding Julie, place incredible importance on. This unfinished composition haunts the film, returning in fragments, refusing to disappear even as Julie attempts to erase every trace of her former life.

Yet we learn early on that some suspect Julie, not her husband, has been the composer all along. This ambiguity is never settled. There is a scene early in the film in which we see Julie looking at a scrap of melody left by her husband on the piano. She hears it orchestrated in her head, and when the written notes end, the camera continues tracking across blank staves as Julie continues to composes the unwritten fragment in her mind.

Kieślowski builds the central tension in the film through Julie’s desire to completely remove all elements of her former life and silence the world around her. She goes to great lengths to disappear, leaving the château in the countryside for an anonymous apartment in Paris. But despite Julie’s efforts to isolate herself and shut out the world, fragments of the unfinished composition overtake her at unexpected moments. When this happens, the screen goes black for a few seconds, as if Julie is being torn from her self-constructed refuge and thrust into a stream of consciousness she cannot resist.

And then at the café near her Paris apartment, there is a repeated encounter with a man who plays a melody on the flute which eerily matches the melody of the unfinished piece for European reunification. She confronts him: ‘How do you know this music?’ to which he responds ‘I invent a lot of stuff. I like to play.’

While rewatching the film, a throughline emerged I had not grasped the first time — in Blue, music doesn’t symbolize meaning; it’s the medium through which being emerges. Kieślowski shows us through Julie’s repeated failed withdrawals that being itself is musical: relational, temporal, emerging through resonance rather than residing in substance. The film asks: what if Descartes was wrong? Not ‘I think therefore I am,’ but ‘I am sounded, therefore I become.’²

I realized while watching that this reversal has radical implications. Music doesn’t wait to be written, it seeks expression through our bodies. When the flute player tells Julie he doesn’t know where the melody came from, he voices the central truth in the film: music moves through us rather than from us. We are instruments, not authors.

Presentational Knowledge and the Birth of Civilizations

The American philosopher Susanne Langer argued that music — alongside dance, painting, and other arts — functions not as ornament or representation but as what she called ‘presentational symbols.’³

These symbols reveal dimensions of reality that discursive language, propositional logic, and mathematics cannot express. Most revolutionary in Langer’s claim is that this revealing is epistemological. Music conveys knowledge just as surely as a mathematical proof or a statement like ‘that rock weighs 37 pounds.’

Langer’s work illuminates what might otherwise seem absurd in Blue: the public’s conviction that this unfinished composition is essential to European reunification. News broadcasters treat the incomplete symphony as if the entire European project hangs in the balance — which, Kieślowski is arguing, it does.

Without music’s presentational knowledge, Europe remains merely a technocratic arrangement. Trade agreements, monetary policy and sophisticated policy arrangements cannot forge collective identity. They cannot make people feel and understand European. Only music, with its capacity to reveal shared temporal experience and ethical attunement, can sound a continent into being.

This is why the commission matters so profoundly in the film. The bureaucrats intuit, without perhaps understanding why, that spreadsheets and treaties alone cannot birth a civilization.

The Primordial Sonic Embrace

Watching the film, I kept thinking about ‘sounding into being.’ The phrase connects to Peter Sloterdijk’s observation in Bubbles⁴ that the human ear is the first sense organ to develop in the womb. We are acoustic beings before we are visual ones. Our earliest experience is immersion in the rhythmic pulse of the mother’s heartbeat and the melodic contours of her voice. This sonic sphere forms what Sloterdijk calls a microspheric dyad: an intimate, pre-subjective interior shared between two bodies. Sloterdijk is radicalizing Heidegger’s Mitsein (being-with) by locating it not in the shared outside world but in shared interiority. In this framing, the first ontological unit is not the individual but the dyad, resonating in a common acoustic sphere.

After birth, Sloterdijk suggests, all our formations — families, tribes, nations — are attempts to recreate that initial sonic embrace. Politics, then, is fundamentally about seeking and nurturing the resonant frequencies that bind us through knowledge and understanding. If Sloterdijk gives us an ontology of resonance, Langer offers its epistemology and method: a theory of how internal feeling becomes symbolically articulated, rendered intelligible, and validated in the public sphere through presentational form.

While watching Blue, the urgency in those TV clips suddenly made sense: the European technocrats intuitively grasp what they cannot articulate — Europe cannot be administered into being through policy alone but must be sounded into existence. Sloterdijk gives us the ontological condition of resonance while Langer shows us how that resonance becomes knowledge, how private affective experience is transfigured into a symbolic order.

The unfinished symphony matters so much because it promises what treaties cannot: a sonic architecture for collective being (mitsein); a vessel through which we hear and imagine ourselves moving through tension and resolution, held together in Gestalt — not in sequence, but in symbolic simultaneity.

The Ethics of What Insists on Being

Towards the last quarter of the movie, in a series of seemingly unconnected events, Julie’s withdrawal finally begins to crack and she finds herself drawn back into engagement with her life.

While consoling her downstairs neighbor in a sex club, Julie glimpses something shocking: her own photograph being shown on the tv in the manager’s office. On the television screen, her husband’s former assistant, Olivier, is being interviewed. We hear him explain that he has recovered the score, which Julie had destroyed by throwing it in a garbage truck earlier in the film. Olivier explains that he plans to complete the unfinished score himself. During the interview, photographs flash on screen. Suddenly, two images appear of her husband with another woman, their faces unmistakably marked by love.

This revelation leads Julie to confront the woman, where she discovers another layer of ongoing life: the mistress is pregnant with her husband’s child.

At this moment, Julie’s withdrawal transforms into engagement. She rushes to meet Olivier, who assumed she had known about the affair all along. She also learns that the copyist had secretly preserved the original scores before she threw the copy into the dump truck. When Olivier plays what he has composed, Julie immediately rearranges it, bringing it into alignment with what came before. Again, we face the ambiguity: was Julie the original composer all along?

With Julie reengaged with the world, she calls her lawyer to reverse the château sale, then invites the mistress over and offers her the house to raise the child.

This is the moment Julie stops trying to silence the world and instead chooses to nurture what insists on being. I read this reversal not as resignation but as radical agency. Julie embraces the fundamental current that runs through humanity from before time: that we are flawed, unfinished, and entangled in permanent ambiguity. The question of authorship — whether of the child or the composition — matters less than the ethical demand of the present: what must be done now.

When Olivier tells Julie, ‘This music can be mine. A little heavy and awkward, but mine. Or yours, but everyone would have to know.’ His insistence on public acknowledgment, that she cannot serve in the shadows, reframes responsibility as recognition. She accepts. This acceptance reveals something crucial: taking responsibility extends beyond one’s own actions to encompass what seeks to emerge through us.

The parallel between the mistress’s pregnancy and the unfinished music becomes clear. Both the child and the composition exceed their origins. The child is more than the product of an affair — it is a human being demanding care. Similarly, music is more than mere content or entertainment, it is a revelation. It is ontological in that it calls worlds into being. It is epistemological because it reveals truths that discourse cannot capture. And it is ethical in that it demands our participation.

The Grid as Ontological Violence

I read this film now as a prescient warning that our post-WWII hyper-idealization of the individual along with the belief that our only responsibility is to ourselves (and through this our ethics are outsourced to the market), leads inevitably to catastrophe. And this is exactly where we find ourselves today.

Like Kieślowski, I believe music holds the cipher through which we can recover our lost ability to resonate together and be sounded into collective being. But this requires spaces where music can still move through us, where we can be surprised by what emerges when we stop curating our lives and start participating in them.

Surprise requires risk, and risk requires trust, and trust requires a culture which is simultaneously confident and humble.

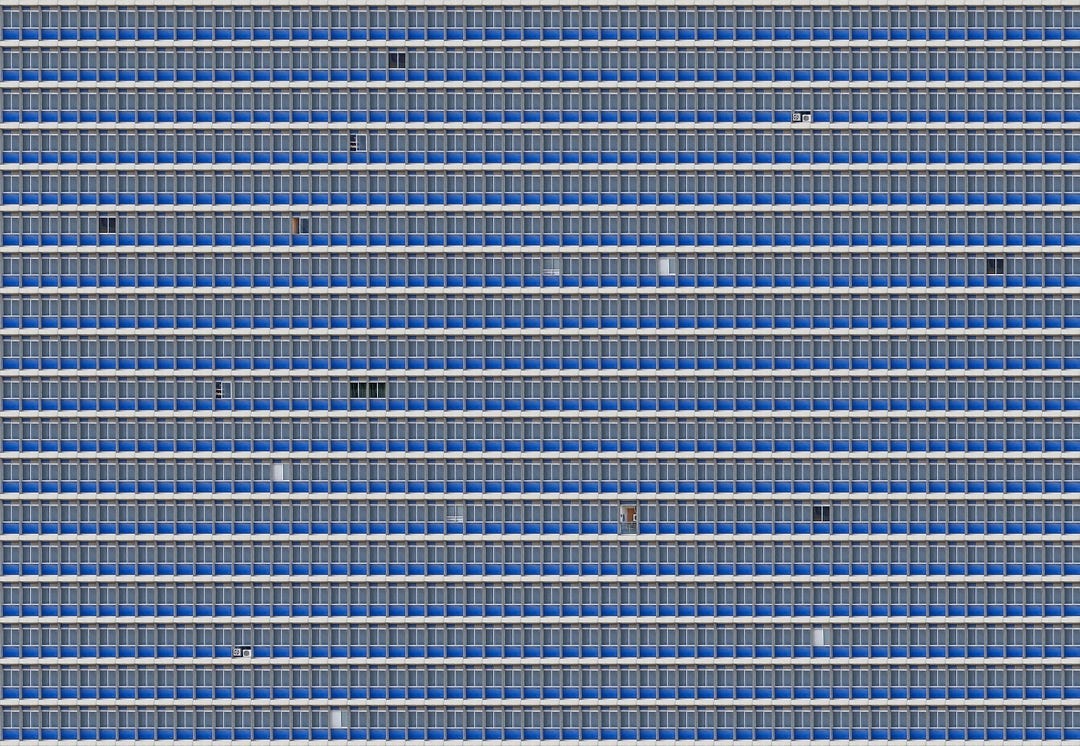

When we put on our Spotify-curated playlists, we engage in an act of withdrawal while simultaneously foreclosing the possibility for new melodies and rhythms — those that seek and need to be heard — from forming. We choose the already-known over the yet-to-be-sounded and in so doing block vital knowledge from being sounded into being. In order for the ‘starving’ musician to eat, they are now compelled to make music that will be placed on these algorithmically curated playlists.

If music is how we’re sounded into collective being, then our withdrawal into private machinic curated playlists undermines the very possibility of democratic life by silencing the public spaces where encounter happens.

Politics can only become legible in public space, where we risk encountering what we didn’t choose to hear. These public spaces can comprise just two people. When we each retreat into our personalized sonic bubbles, we lose the very ground where collective meaning can emerge. The street corner where the flute player performs, the concert hall, the local show where you encounter what an algorithm would never risk serving you — these are the spaces where democracy is literally sounded into being.

So what can be done to reclaim these spaces where music moves through us, rather than being served to us by algorithms that know only our past, never our potential, and seek only to extract our digital data trail?

I believe musicians must make a radical choice: to exit the online ecosystem entirely. To release music only in physical spaces, where bodies gather and risk encounter. But isn’t this just an extreme form of nostalgia or Luddism? No. Like Kieślowski, I view this as an act of responsibility.

To support this transition we need to (re)build the infrastructure for offline musical discourse. To encourage the formation of spaces where sound can do its ancient work of affirming and enlarging our collective experiences and support the musicians who are risking the creation of this vital knowledge.

But beyond that, musicians, producers, and studio owners need to understand their responsibility and reflect upon modern recording methods which embrace technology that flattens human expression in the name of efficiency and ‘accuracy.’

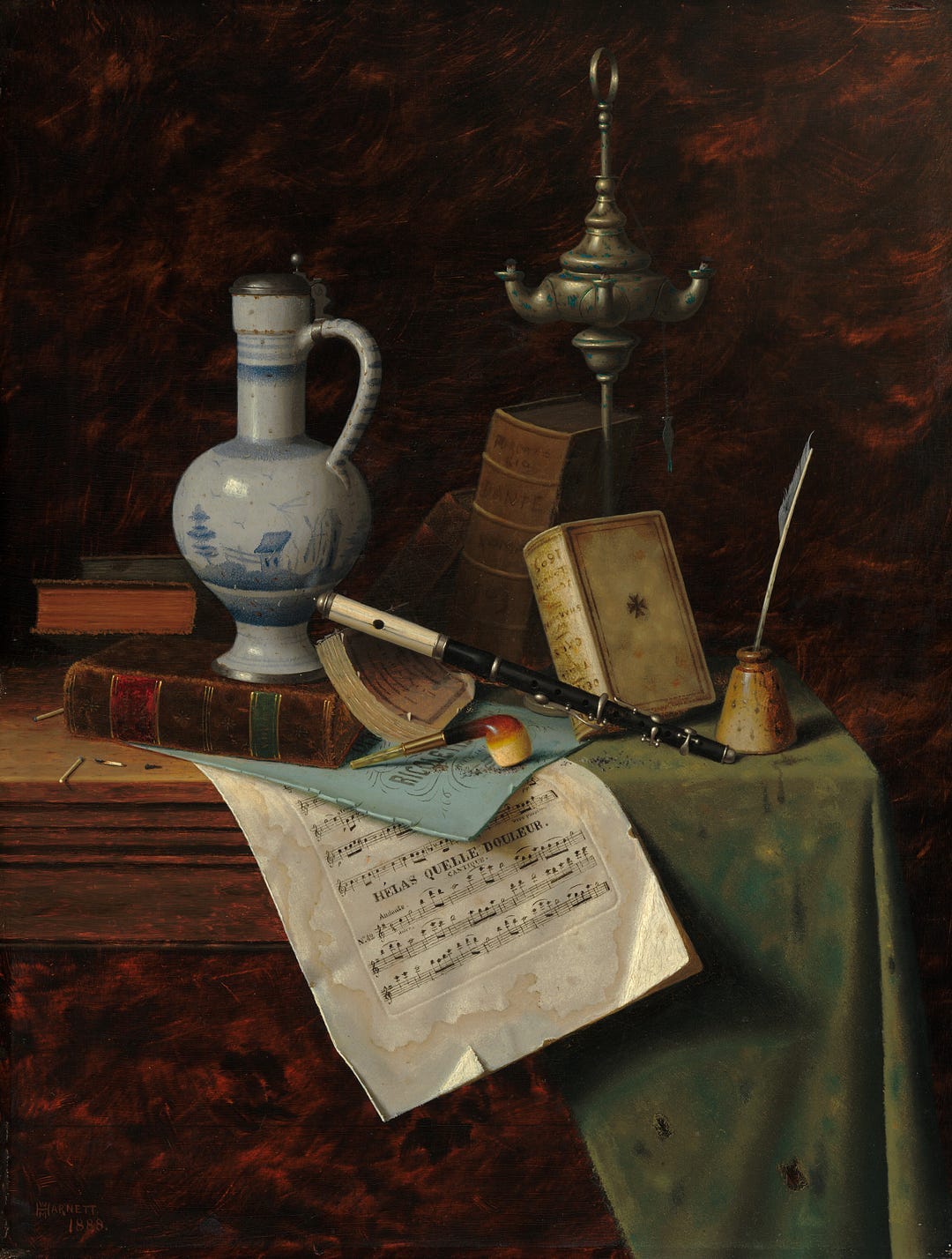

These modern production methods — where people record a single song in different studios around the world, never sharing the same space, their tracks subjected to the almighty ‘grid’ of Pro Tools — must be reconsidered. When performances are ‘fixed’ through manual autotune, where producers draw in pitch to correct actual performance,⁵ or when drum tracks are subjected to Beat Detective⁶ and quantized with a 2–3% ‘humanization’ rate to simulate embodied ‘imperfection’, we engage in a form of ontological violence.***⁽ˢᵉᵉ ᶠᵒᵒᵗⁿᵒᵗᵉ⁾

I see a throughline from this violence in the studio manifesting in our political fractures. The Red versus Blue divide, the global rise of nationalist movements, the inability to hear each other because we don’t have the cipher to decode difference: these are not separate from our musical practices. They are its direct consequence⁸. When we lose the ability to be sounded together, we lose the ability to be together at all.

The Possible and the Real

Kieślowski saw this coming. In 1993, he understood that an integrated post-Soviet Europe needed actual music, not spreadsheets, charts and sophisticated policy arguments. For a project like that to succeed it needed to be sounded into being — a resonance which gestures toward the only universal humanity shares outside death: our mother’s sonic embrace.

To help achieve part of the vision I have been tracing here, I’m building an offline-only record label, launching in summer 2026. This feels increasingly urgent as AI-generated music floods streaming platforms with at least 20,000 songs daily.⁹ Spotify claims that 100,000 new songs are uploaded every single day and is now publishing AI-generated songs from dead artists without permission.¹⁰ In the context I have outlined above, this shows we are drowning in content yet starving for meaning.

That initial reaction I had as a teenager watching Blue for the first time — ‘I didn’t know you were allowed to live this way’ — captures precisely the sort of rupture that is rapidly being flattened out of existence in favor of the curated, the safe, the familiar.

A podcast host recently said: ‘Art reveals what is possible and through revealing the possible, reveals the real.’¹¹

The first time I heard this, I was confused. How can revealing the possible reveal the real? But that is exactly what the flute player on the street corner was doing. When Julie asks, ‘How do you know this music?’ she’s really asking how he can channel what doesn’t yet exist yet that she herself knows is real. The answer is that both Julie and the flute player were pulling into presentational symbolic form what their culture fundamentally internally felt but had not yet articulated.

But we now live in a world mediated by algorithms within a political economy that requires algorithmic visibility for survival. What happens to all the music that would have given form to our emerging feelings and intuitions when musicians must write for the algorithm instead? When the possible remains unsounded, when no one risks bringing forth what we collectively sense but cannot name, confusion and anxiety fill the void. Violence follows.

As Susanne Langer warned in 1958:

‘The arts objectify subjective reality, and subjectify outward experience of nature. Art education is the education of feeling, and a society that neglects it gives itself up to formless emotion. Bad art is corruption of feeling. This is a large factor in the irrationalism which dictators and demagogues exploit.’¹²

These are the stakes Julie came to recognize. The question remains: will we come to our senses in time?

*** This violence can be understood through Bernard Stiegler’s concept of the pharmakon⁷, technologies that function simultaneously as poison and remedy. ‘Pharmakon’ draws from Plato’s Phaedrus, where writing is depicted as both remedy and poison for memory. Stiegler extends this to technics broadly where every technological supplement introduces both care (curation, retention) and harm (disruption, loss). Digital production tools aren’t inherently destructive; they extend creative capacities and enable new expressions. Yet their uncritical deployment transforms potential remedy into poison. When we prioritize technical perfection over lived resonance, we replace being-together-in-time with synchronization without encounter. The grid in this context escapes the technical and becomes ontological, flattening the very temporality that gives music its power to sound us into being.

Citations

¹ Kieślowski, K. (Director & Co‑Writer), & Piesiewicz, K. (Co‑Writer). (1993). Three Colors: Blue [Film]. mk2 Productions; CED Productions; France 3 Cinéma; CAB Productions; TOR Studio Production; Canal+. https://mk2films.com/en/film/trois-couleurs-bleu/

² Descartes, R. (1995, June 28). A discourse on the method of rightly conducting one’s reason and of seeking truth in the sciences (J. Veitch, Trans.) [Project Gutenberg eBook #59]. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/59/59-h/59-h.htm (Original work published 1637)

³ Langer, S. K. (1953). Feeling and Form: A theory of art developed from Philosophy in a New Key. Charles Scribner’s Sons. https://archive.org/details/feelingform00susa

⁴ Sloterdijk, P. (2011). Bubbles: Spheres Volume I: Microspherology (W. Hoban, Trans.). Semiotext(e). (Original work published 1998)

⁵ Sweetwater. (2020, November 27). How to auto-tune vocals using Antares Auto-Tune Pro [Video]. YouTube.

⁶ Mix With Jacob. (2023, January 3). Fast quantizing using Pro Tools’ Beat Detective! | Quantize your drums in less than 5 minutes! [Video]. YouTube.

⁷ Stiegler, B. (2019). The age of disruption: Technology and madness in computational capitalism (D. Ross, Trans.). Polity Press. (Original work published 2016)

⁸ Anthony, J. (2024, September 17). Red vs. Blue: Is modern music production driving our political divide? Counter Arts. https://medium.com/counterarts/red-vs-blue-is-modern-music-production-driving-our-political-divide-50fec9b1da60

⁹ Robinson, K. (2025, April 16). Deezer says number of fully AI-generated songs delivered daily has doubled since January. Billboard. https://www.billboard.com/pro/deezer-fully-ai-generated-songs-uploaded-daily/

¹⁰ Maiberg, E. (2025, July 21). Spotify publishes AI-generated songs from dead artists without permission. 404 Media. https://www.404media.co/spotify-publishes-ai-generated-songs-from-dead-artists-without-permission/

¹¹ Ford, P., & Martel, J. F. (n.d.). Weird Studies [Podcast]. Weird Studies.

https://www.weirdstudies.com/

¹² Langer, S. K. (1964). The cultural importance of art. In Philosophical sketches (pp. 75–84). New American Library. (Original work published 1962)